The bad news for Swiss farmers is good for consumers who pay the highest food prices in Europe.

A tariff system created to preserve Switzerland’s farm industry effectively prohibits imports if a product can be produced domestically. Conversely, if poor harvests or increased demand result in a scarcity of meat, fruit, and vegetables, levies on cheaper imported items can be reduced.

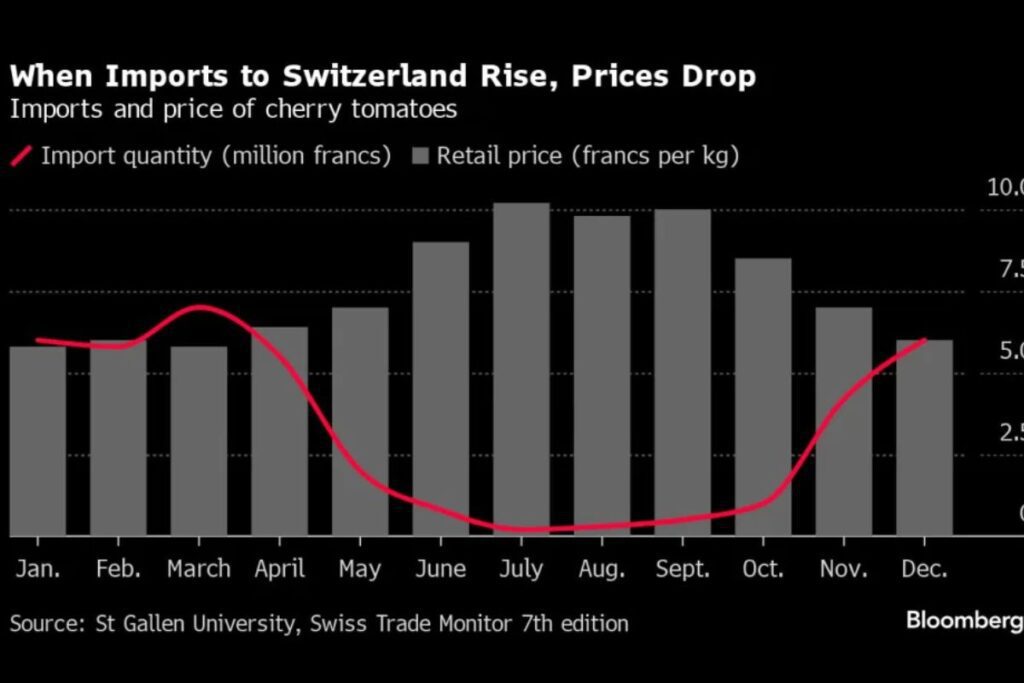

“In the summer, when domestic products hit the market, prices rise,” said Maxime Botteron, an analyst at UBS. “It’s exactly the opposite of what happens in the surrounding euro zone, where prices drop if internal supply rises.”

Swiss Farmers and Shoppers with Cheaper Tomatoes

As a result, crops like cherry tomatoes are typically cheaper when they are out of season.

The government, under pressure from the country’s powerful agriculture lobby, maintains this seeming paradox in order to safeguard local farmers and assure food independence. Consumers have generally accepted the compromise, especially as inflation has stayed far lower than in the eurozone.

“Swiss products are associated with high quality, as well as high environmental and social standards,” stated Stefan Legge, head of tax and trade policy at the University of St. Gallen. “A large part of the Swiss population is just ready to pay those high prices for that.”

The government regularly reduces levies, but only in specified instances. This was the situation last week with eggs, as Swiss chickens were unable to meet demand despite a 35% rise in local production over the previous decade. To secure supply before Christmas authorities increased the annual limit for reduced-tariff imports by 43% to nearly 25,000 tonnes.

Despite the system’s protections, Swiss farmers claim they still struggle to make a livelihood. Last year, the government provided direct subsidies to agriculture totaling 2.7 billion francs ($3.1 billion).

During a visit on Friday to a farm in Wileroltigen, a community of 379 inhabitants nestled against the background of the Alps, most complaints addressed to Economy Minister Guy Parmelin were about overwhelming bureaucracy and strict pesticide rules.

He admitted that prices are an issue, but said that Swiss foods fulfill higher criteria and emphasized the need of food security.

“We produce in a country where the costs are high,” the former winemaker told journalists. “We have to maintain the border, that’s our insurance to keep production in Switzerland.”

The desire to be independent from others is strongly ingrained in the 220-kilometre-wide (140-mile-wide) landlocked country, which remained neutral throughout two World Wars and is the only major state in central Europe not to have joined the EU.

According to Legge of St. Gallen University, high local salaries mean that many Swiss customers may be unaware that they are spending approximately 50% more for food than their neighbours.

And those that do may always cross the border and shop in France, Germany, Italy, or Austria. Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

Read more

Lamborghini CEO Unveils New Hybrid Supercar: How the ‘YOLO’ Effect is Driving Sales Growth

Ukraine says it sank a Russian submarine by missile strike in Crimea

Daisy Morgan is a dedicated business journalist known for her insightful coverage of global economic trends and corporate developments. With a career rooted in a passion for understanding the intricacies of the business world, Daisy brings a unique perspective to her writing, combining in-depth research with a knack for uncovering compelling stories. Her articles offer readers a comprehensive view of market dynamics, entrepreneurship, and innovation, aiming to inform and inspire professionals and enthusiasts alike.